Today I have a real treat for you guys. I’m delighted to host a guest post by Harry Connolly, author of the Twenty Palaces series, and The Great Way, his new fantasy trilogy. I’ve been a fan of Harry’s for years, and was thrilled to be able to participate in Harry’s blog tour. He has written a dynamite post on pacing in fiction, so you writerly types take special note. And be sure to follow Harry on Twitter @byharryconnolly and follow his blog, Harry J. Connolly. And go read his books! They’re fantastic and imaginative and great fun. Now, on to Harry’s words of wisdom!

He Always Runs While Others Walk: Pacing in Fiction

We’ve all had the experience of reading a book all the way through to the end because we just have to get to the end. God help us, the awful word “unputdownable” was coined just for this, and as much as I hate the word, it exists for a reason.

Pacing. For the sort of fiction I write, it’s vital, but I think it’s also misunderstood.

Typically, people talk about pacing when they talk about my style of writing—chases, fights, daring escapades—but every book has its own pacing. If we’re reading about a young woman spending a summer in Florence, you’d expect the pacing to be mellow and relaxed, with a text mainly focused on description and casual conversation. Likewise, most cozy mysteries are chiefly made up of conversation and scene description, which are not usually considered gripping entertainment.

And yet, just like with thrillers, we can find ourselves compulsively reading cozies.

In other media, pacing can be pretty straight forward. How do we pick up the pace in music? Have the drummer (or the other musicians) play faster. (Probably there’s advice about playing on the upbeat instead of the downbeat, but I’m not musical.) Film has a number of techniques, including fast editing, that will speed the pace.

But with text on a page, it’s just one word after another. We can make a book seem shorter by including a bunch of one-line paragraphs that don’t extend to the right margin, but that’s just the book. It doesn’t increase the pace of the story. Yeah, I’m going against some really common advice here: short sentences are not one of the keys to fast-paced writing. We can increase the pace with long sentences, too. I ended the biggest action scene in Game of Cages with a run-on sentence that was over five hundred words long. It’s complexity, not length, that slows things down.

My friend Bill Martell is a screenwriter with an interesting theory (well, more than one, really, but let’s talk about this one) about films: they generally have two genres. The primary genre is where all the big set pieces and high drama occurs. Those are the super-exciting “peaks” in the story where the pace is most frenetic. The secondary genre (the word “subplot” just isn’t that descriptive) is where the “lulls” happen. Taking Super-8 as an example: the primary genre is a monster movie about an alien that grabs people and devours them. The secondary genre is a coming of age story. In between the chase scenes and the scary monster stuff, the mellower moments that let us catch our breath center on the protagonist’s relationship with his father, with the girl he likes, and with his best friend.

In decades past, the second genre was typically a love story, usually with the Only Woman Appearing In The Film. Lately, it’s more likely to be about Daddy Issues.

Books are different, but only because they can be longer and more complex. We can have a whole bunch of different plots running throughout the book, with multiple points of view, and can switch between them whenever we need to alter the pace. If we have one storyline about a prince leading a battle against an invading army, we can switch over to the princess being forced into a marriage with a man she knows is secretly plotting with the invaders, then switch to a disreputable smuggler working the docks, wondering who’s bringing in all these new shipments. Battle -> Court Intrigue -> Skulking -> Battle -> Court Intrigue -> and so on, switching between them.

The thing is, each storyline could be equally gripping. Just because one is slower-paced than the others doesn’t mean that the reader attaches to the story less ferociously. But the difference in pace is important for creating that reader attachment. The fast parts need the slow, just as the slow needs the fast.

To shift gears a little bit: Most people who go to see a Michael Bay movie know they’re in for spectacle, which is achieved through some very specific techniques. However, although the pace is fast due to the way it’s framed, shot, and edited, a lot of people find it intensely dull and/or unsatisfying.

The audience doesn’t care because the first step in creating pacing that really works is to create a situation that the readers care deeply about.

Look at the situation I presented four paragraphs before: some readers will have zero interest in anything related to a princess forced into a bad marriage. Maybe they don’t like reading about female characters. Maybe they don’t like reading about female characters without a lot of agency. It doesn’t matter. Even if the story is full of chases and betrayals and death-defying risks, every time the narrative switches to her plot, the book will sag.

For that reader.

You really can’t please everyone. Personal example: I was confused by early reviews of Child of Fire that said “nothing happened” for the first 100 pages. I was perplexed by this, because the protagonist sees a child catch fire and transform, they he helps break into a home, then a gunman shoots up the restaurant he’s in, then…

Anyway, a lot was happening, and it was happening quickly. However, the main plot question was “What the hell is going on here?” and there are certain readers who don’t consider that a legitimate plot question. For them, unless there’s a clear goal (beyond “we need to figure this out”) it’s all a holding pattern. I suspect those readers will never truly like my work.

How do we control the pacing, though?

As I’ve been trying to demonstrate, there are no hard and fast rules. Some choices will seem fast in one book and slow in another, depending on what’s around it. Sometimes the reader will be impossible to win over, no matter what we do.

Like all writing, it depends on what information is being delivered to the reader and how. It’s not something I can turn into a numbered list. Is the scene we’re writing about a soldier trying to defuse a ticking bomb, and full of relatively simple language? Probably fast paced. Is it about a soldier trying to defuse a bomb and full of complicated clauses, digressions into the soldier’s childhood, a description of the surroundings? Well, that might be frustratingly in conflict with itself, and maybe that’s the point.

Characters we care about, doing something we’re interested in, acting in a frantic way, described in the appropriate language, is probably a fast-paced part of the story. Unless it isn’t. If they’re taking stock, or just getting to know each other (so the reader will be sad when they’re killed later) that’s probably slower.

The only way to really tell is by the feel of it. When writing/revising/rereading a section, do we feel as though some tidal force is pushing us forward? Do we feel centered and at ease? Frankly, for all the talk about writerly technique, I think we too often give short shrift to the true arbiter of proper technique: our own taste.

Short sentences! Showing instead of telling! Whatever! These things are usually substitutions for the careful creative decision that seems right at the moment. The real world of art—even commercial art of the kind I write—is more complicated than short sentences = fast pace.

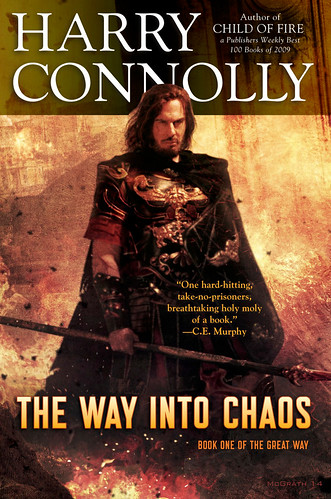

Anyone who’s curious about the way I do pacing, look no further than the opening of my new trilogy. Check the cover.:

It’s about a sentient curse that brings about the collapse of an empire, and it received a starred review from Publishers Weekly.

You can find out more about that first book here, or you can read the sample chapters I’ve posted on my blog to see a slow lull that builds until it turns into a fast-paced scene of violence.

Thanks for your time.

BIO: Harry Connolly’s debut novel, Child of Fire, was named to Publishers Weekly’s Best 100 Novels of 2009. For his epic fantasy series The Great Way, he turned to Kickstarter; at the time this was written, it’s the ninth-most-funded Fiction campaign ever. Book one of The Great Way, The Way Into Chaos, was published in December, 2014. Book two, The Way Into Magic, was published in January, 2015. The third and final book, The Way Into Darkness, was released on February 3rd, 2015. Harry lives in Seattle with his beloved wife, beloved son, and beloved library system.